Okay, so Saltburn might not be as hot on everyone’s lips as it was when it dropped on Amazon just before Christmas, but I only just got to watching it because nobody told me it was a gothic film. A gothic film? If I’d known that, it would have earned an immediate Go-Straight-to-the-Top-of-my-Watchlist ticket without passing go. Unconvinced? Do the neon club scenes of the first five minutes have no place in the gothic canon? The almost-contemporary mid-00s setting? Ah, but what about the references to Shelley and Byron? What about that bloody scene on the garden bench, or that, ahem, penetrating scene on the fresh grave?

Let’s take a scalpel to Saltburn and see what tropes of the gothic tradition we can lay out on the slab.

Saltburn

In naming itself after an ancestral home, Saltburn joins itself with some familiar titles in the gothic tradition: Northanger Abbey, Gormenghast, Rawblood, Crimson Peak… It’s a kissing cousin to even more – The Castle of Otranto, The Mysteries of Udulpho, The Fall of the House of Usher – and joins Manderley and Bly Manor as the seat of a rich family and a corporeal symbol of their legacy. Like the aforementioned piles, naming the house makes Saltburn is a character in its own right: a warren of wealth standing above and untouched by the seductions and Machiavellian plots within it. It stands like a stone in a blood and tear-stained river.

The intro titles, framed as Oliver walks around Oxford’s Radcliffe Camera, are splattered across the screen in red Olde Englishe font, the kind of thing you might expect from a Hammer production of the late 50s. Oliver even makes a deadpan quip about what typefaces look good on headstones later in the film. Speaking of Hammer – shot in 4:3, Saltburn’s own presence on the screen better fits the pre-widescreen television world of Hammer House of Horror. From the start, Saltburn wears its gothic heart on its sleeve.

Rogue’s Gallery

In Saltburn, we see a cast of characters conforming to archetypes in the gothic tradition. Oliver, our narrator, presents a scholarly, bookish hero – an academic out of M. R. James, perhaps. As the film goes on, we see some chivalry in him too, some kindness, some tragedy. His new friend Felix is a Byronic man, for whom sex is as easy a conquest as ordering his omnipresent Lurch-esque butler to send a car to collect Oliver. As the narrative shifts from Oxford party to the Saltburn Estate, we meet Felix’s father – a Mervyn Peakean eccentric – and mother, an out-of-touch, easily swayed and seduced heiress. But its Felix’s desperate sister (“sexually incontinent”, warns Lady Elspeth) who provides so much gothic aesthetic, whether it’s wandering, somnambulist-style through the misty ground, or reclining in a see-through gown beneath Oliver’s window.

As the story progresses, Oliver takes on another familiar gothic mantle – that of the antihero. His assimilation into Saltburn is not unlike Heathcliffe’s in Wuthering Heights. From the start of the film, we see his cigarette burning red in the darkness as he spies on Felix in his rooms – he is a flawed protagonist, driven by a cold heart and a dangerous obsession.

Amor E Morte

I’m avoiding spoilers in this autopsy of Saltburn, but look: there are deaths. People die. Murders? Who mentioned murders? Let’s call them deaths and leave it at that. There’s also sex – a fair dollop of it – and these two presences enjoy lots of screen time together. This peaks (Peakes?) in one particularly bold scene with a grave marker, freshly dug-earth and an… insertion. But this scene aside, it’s a recurrent motif.

When Oliver and Venetia first kiss (sorry, SPOILERS, but if someone recommended you Saltburn they told you about this scene), the menstrual blood he smears on their lips symbolises how far Oliver is willing to push to get what he wants, and it also evidences the terraced symbols of sex and death. There’s a precursor to this scene – or at least, the act depicted – in 1986’s Gothic. Gothic is the story of the Shelleys and Byron in their Geneva lakehouse and they are casually namedropped in Saltburn, making for a knowing reference. Of course, the Gothic scene is shown in less graphic detail. Saltburn is a creation of the 2020s, and can be more explicit in its content. The aforementioned grave scene shows what Bronte couldn’t in Wuthering Heights, when Heathcliffe digs up Cathy’s grave to take some comfort from her corpse. In Saltburn, things are much less ambiguous.

The Blood is the Life

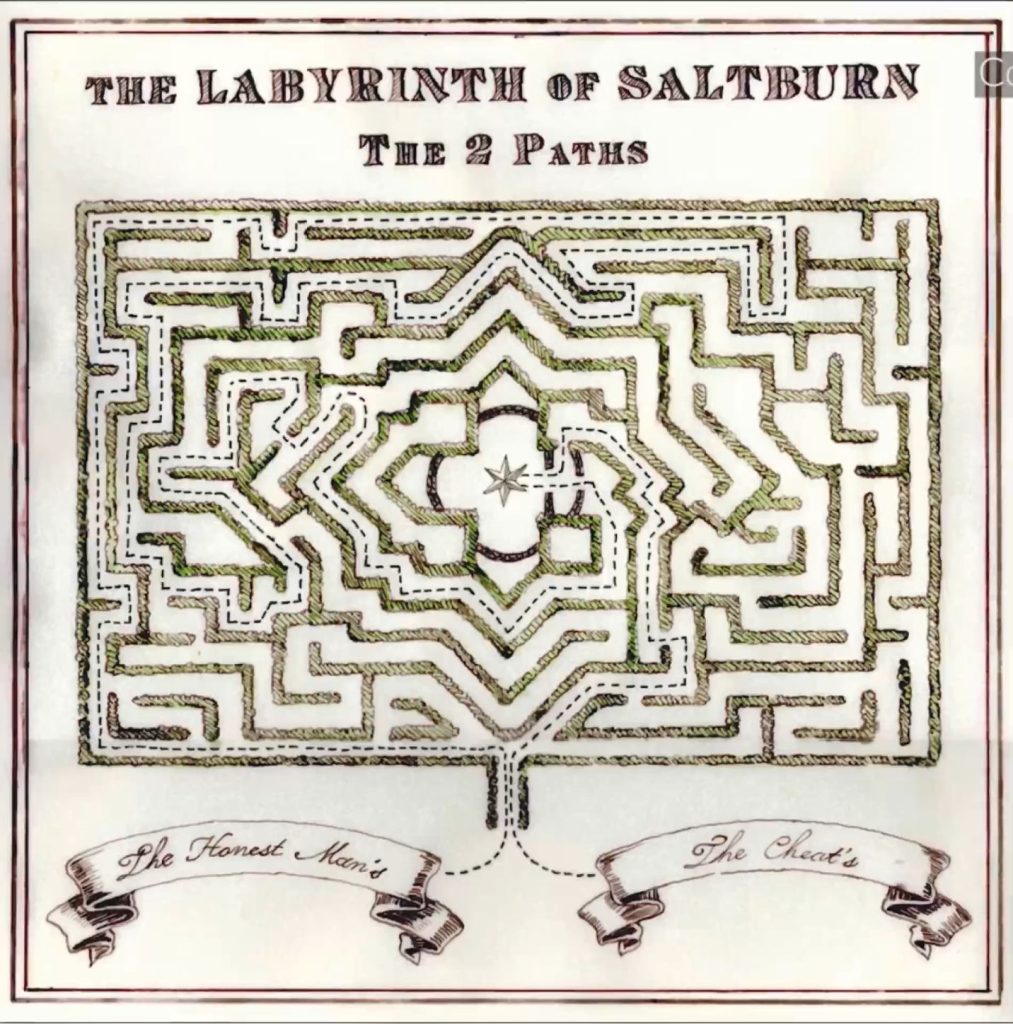

“The vampire scene”, where Oliver goes down on Venetia, trended on social media, and makes explicit the link between Saltburn and a gothic horror classic: 1992’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Vampiric head aside, references to Dracula are copious. Saltburn’s maze, and the camerawork amongst its hedges, are heavily reminiscent of the scenes in Dracula where Lucy and Mina are seduced by the titular count. Venetia’s overflowing wineglass hearkens to Dracula’s dripping blood candles. When Saltburn’s blinds are drawn, turning the dining room crimson, its not unlike the colourisation of Dracula. There’s even a cheeky transition from a party scene in the house to a closeup of a pig spit roasting outside, a trick employed in Dracula also (though perhaps without the innuendo).

Director Emereld Fennell confirms that “metaphorically it is a vampire film” and, in its course, it’s easy to see that characters are allegorically (and occasionally physically) sucking each other dry.

The New Gothic

So. Saltburn is definitely – nay, primarily – in the gothic tradition, and I won’t have it any other way. There have been several modern takes on gothic, whether it’s in the form of Tim Burton’s stripey cinema or iconoclastic authors like Sylvia Moreno-Garcia, who take gothic tropes and relocate or reframe them in new ways. But Saltburn remembers that gothic began as something shocking, grotesque and even disgusting, even if it’s becomes something historical, mannered and classy. Gothic literature pre-empted horror, and even if it wasn’t explicitly horrifying by today’s standards, it did make explicit certain sexual or visceral acts and incidences – at least, as much as its time allowed.

Saltburn isn’t a horror film, but like literary gothic, it uses the taboo of today to shock and disgust its audience. Hot on the heels of Netflix’s The Fall of the House of Usher, another gothic revival that amplifies the explicit content which its original author could not, it begs the question – is the world ready for gothic to shock it all over again?